Echoes of Legend: Symbolism and Patterns in African Myth

How Myths Forge Identity, Illuminate History, and Reveal Enduring Philosophical Truths

Introduction.

There are two foundational myths we’ll explore through the lens of one. These tales too often are overlooked, not by their descendants but by those with the broadest platforms to share them. Spanning West, Central and East Africa, these stories carry profound cultural, educational and political weight. By revisiting Bida and Diagay we uncover not only the recurring motifs of love, sacrifice and supreme beings, but also the deep philosophical intent woven into each narrative. Far from primitive taboos, these myths reveal a rich, sophisticated philosophical vision and by restoring them to the classroom, the lecture hall and the screen, we can dismantle the stigma that has long silenced Africa’s own storytellers.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks is our own intent as Africans: even when these stories are retold, they’re conveyed with so little richness that they fail to craft the self‑image we so desperately lack. That deficit leads to more pride in Western or colonial narratives and a general disinterest in the very medium that carries these tales. This is not to say descendants haven’t tried many have, and those individuals form the reference base for this article, building on previous efforts. There’s genuine interest in these myths, but often their retellings are confined to children’s bedtime stories or kin‑circle fireside talks. Ask the average educated relative from the story’s homeland and, chances are, they know more about Greek mythology or even Westernized Egyptian lore.

Much has been delved into about Egyptian mythology from a Western perspective and scholars like Cheikh Anta Diop have worked to accurately reclaim the stories and stake of Black Egyptians.³ To highlight my key assertions, I’ve deliberately avoided Egyptian myths here perhaps a topic for later and instead chosen four Sub‑Saharan tales that reveal unique depth and an even more advanced precolonial psyche. Furthermore, these stories are littered with truths if you look at them as mythologies: we don’t literally believe there was a giant cyclops or that Achilles was Zeus’s son, but those tales built children’s bravado and crafted self‑image an image whose long‑term implications reverberated in Western thinking, guided by cultural pride and what I’ll call high cultural esteem, which then fueled colonization and subjugation.

I will show that through political, cultural and social lenses, these myths offer far more than children’s stories or a fireside yarn from your grandfather heard once a year between Christmas and New Year before you’re thrust back to the capital and fed history based on liberation party narratives or everything about British kings who looked nothing like you, further lowering our cultural esteem with disastrous consequences.

One Particular African Myth

“The Golden Serpent” by Harmonia Rosales. Image courtesy of the artist. www.harmoniarosales.art

Bida, the Seven‑Headed Serpent of Wagadu

The particular lore we will explore about Bida, the seven‑headed serpent, comes from the Soninke people of the western Sahel, primarily in what is now Mali and Mauritania, with communities across Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Ghana. They were the foundation of the great Ghana Empire, and this folklore is meant to craft pride in a people, shape identity, and, above all, offer philosophical insight. Bida was the foundational serpent that brought prosperity to the empire through its many gifts. It had seven differently colored heads, each representing distinct powers and responsibilities among the Soninke.¹ The story goes as follows:

The legendary founder‑king Dinga forged a sacred alliance with Bida (also called Miniyan in Soninke). Bida assumed the role of a deity of the land. Like most pre‑Abrahamic religious deities, one common theme emerges: these beings displayed human tendencies, even mortality. Christ became mortal according to Christianity, but that was willful. To continue with the story, as long as the Soninke offered regular sacrifices of the most beautiful maidens in the land, Bida ensured abundant rains, fertile harvests, and the appearance of gold in the fields after each downpour.² Through this bond, Wagadu flourished for generations, its wealth and security woven into the coils of the serpent‑god. We know from further lore that Dinga himself was worshiped as a deity. Ceremonies and festivals were held in tune with the seasons to appease Bida. We won’t dwell on historical accuracy of the varying versions for that bears no importance here but rather on the intricacies of the lore as myths take diverging turns based on the needs of the folk crafting them or rather reciting.

Centuries later, Wagadu had grown complacent under Bida’s guardianship. When famine threatened, Lagarre, Dinga’s grandson, found the vast serpent sleeping at the city gates. In some versions of this lore, this episode is omitted entirely, but here Lagarre awoke Bida and negotiated a new deal: instead of ten maidens a year, the kingdom would send just one and she had to be the fairest of them all, pure and clean. “Cleanliness” in this sense meant having a good heart and coming from a proper family in exchange for three showers of gold annually.⁴ Bida agreed, and for a time the golden rains continued to bless Wagadu’s plains. By custom, the next first‑born female in Wagadu was designated for sacrifice though some versions simply state she amazed all who saw her face. That year, the honor and the terror fell upon Sia Jatta Bari, celebrated as the fairest maiden in the realm. Draped in white and led in bridal attire to the deep well outside the city, Sia embodied both the kingdom’s devotion and its dread.⁵

Sia’s betrothed, Mamadi Sefe Dekote, was, of course, horrified, for he loved his bride. In Ghana Empire lore, Mamadi is called an orphan, yet elsewhere his mother appears, cautioning him and knowing him personally. Orphan or not, he was known to keep his word. A Soninke version of the Ghana Empire noted that he “never said more than two words,” not because he was a habitual mute, but because his word was its own guarantee he needn’t say no more.⁹ In other words, he was a principled man. From listening to HomeTeamHistory on their YouTube channel, which did an in‑depth study of this lore, we learn that Mamadi was a warrior and a hardworking man in his own right. Versions that paint him as an orphan describe someone who rose from great strife to undertake the hero’s journey and become who he was as orphans in lores do.

As the story goes, Mamadi sneaked toward the river on the night his betrothed was to be consumed by the serpent. Knowing him as a man of his word, his beloved had begged him to let her meet her fate for the sake of her people. Aware of the disaster that would befall them if she were not sacrificed to Bida, the god‑serpent, she accepted her role with honor. But Mamadi who had earlier told her of his plan to save her need not say more than what he was prepared to do. When she was cast into the river for the ceremony, the riverbed is said to have emptied, and the serpent emerged, mystique and menace in tow, ready to devour this radiant and aesthetically pleasing being. Yet Mamadi had spent the better part of a week forging a razor‑sharp sword, working off the blacksmith’s provisions and wages to earn the blade proof of how much his bride meant to him.

We’re told he hacked off head after head of the serpent until, at last, this seven‑headed god‑serpent immune to ordinary death, especially at the hands of an assumed orphan fell. In true epic fashion, the ground shook and a great light roared as the beast was slain.⁶ To further defy the elders he left behind, he gave his bride one of his shoes (him being the only person who could fit it), so that when the elders scoured the land for the perpetrator of this act that brought drought, famine, and the loss of gold, prosperity, and wealth, they would find him at once. It was like Olenna Tyrell telling Jaime to inform Cersei, “I want her to know it was me.” Thus, Mamadi’s defiance was sealed: first wealth, then sacrifice, then love. There was a price, for demise visited the land all in the name of love.

Other versions that reject the orphan narrative say his mother confronted the elders before they could slay her son, using her wit to shame their manhood and offering instead to shield the empire from seven years of demise in exchange for forgiveness. But most versions end with Mamadi and his beloved riding away together, their love and passion prevailing over all. A love so strong that a man who only ever uttered the words he meant to keep was willing to pay the serpent’s price in exchange for his bride’s beauty because she was worth it.

Disambiguation ; King Isaza

In reexamining one popular myth that I was taught during my primary education in Uganda I want us to look at three recurring themes: love, sacrifice, and prosperity, which is a common theme in these African foundational myths. These three themes will then guide our understanding of the points I am to convey. Furthermore, I picked this particular myth to use it, rather as a disambiguation of the myth of our prior god‑serpent (RIP); hence, this version I present is as remembered from Mrs. Florence’s classroom in Kampala Parents School (begrudgingly, as no teacher caned me in primary school more than her).

So as it goes, Omukama Isaza Rugambanabato ascended the throne of Kitara as a young warrior‑king, his fame spreading far and wide. Intrigued by tales of his prowess, Nyamiyonga, the formidable ruler of the underworld, sent a cryptic challenge in search of uniting both the underworld and Isaza’s upstairs realm. One morning, Isaza received a royal messenger bearing six riddles: the measure of time, the rope that binds water, the thing that turns a man to look behind, the one who shirks all duty, the one perpetually drunk, and the door that locks out poverty.⁷ No explicit request accompanied them; Isaza was expected to deduce Nyamiyonga’s desires.

Puzzled, Isaza first called his elders in council, but they offered no answers, as was the case with Nebuchadnezzar and his wise men (Elders’ councils were historically always wrong in a lot of lores). It was only when a wise maid brought forward everyday scenes showing a calf’s lowing to explain what makes Isaza look back, and a dog with a smoking pipe for one who shirks duty that the riddles fell into place. Each answer revealed some truth of the human condition, from joyless drunkenness to the bonds of kinship.

“Even Isaza would’ve followed these horns into the underworld.”

Nyamiyonga, being the schemer that he was for no daft man kings the underworld, learned that Isaza loved cattle and women above all else. Looking to ensnare the upstairs king, he first brokered a blood pact not with Isaza himself but with Bukuku, a commoner minister, dishonoring their bond. Then Nyamiyonga dispatched his daughter, Nyamata (Hello, Delilah? Does it ring a bell?), whose very name means “of milk,” to Isaza’s court. Unrecognized, she enthralled the king with her stunning beauty (for milk and honey are often associated with an abundant land, the girl’s name translated into milk, beauty abundant). Isaza married her without a second thought or much agitation to any resistance, believing her a mortal princess; only later, when he discovered her true parentage, did he grasp the underworld’s design and schemes.

In Nyamiyonga’s chamber, the first fruits of their union appeared: a son, Isimbwa, born of both cow’s milk and royal blood. Still, Nyamiyonga was not yet satisfied. He tested Isaza’s devotion by sending two prized cattle from his own herds, Ruhogo the bull and Kahogo the cow, to wander among the king’s flock. Then, as they appeared, they disappeared, and with his beautiful Nyamata did they vanish. When Isaza tracked the strays into a hidden portal (for they had turned his head, remember the riddle?), he found himself in Nyamiyonga’s realm, reunited with Nyamata and their son, but barred from return by the broken pact.

Isaza’s entrapment was complete: day after day, he groped through the darkness of the underworld, shaking the earth above with his futile quest for daylight. Back in Kitara, Bukuku seized the throne, and the kingdom passed to a new line. Thus the myth endures among the Banyoro: a caution that even the greatest king can be undone by riddles of fate, the lure of the underworld, and the very bonds meant to sustain him.

Symbolism of Myths, Pattern and Philosophical Implications

Myths have a symbolic pattern about them, and they aim to convey truths. A lot of the characters in myths are rather true, but as the sands of time degrade the buildings and erase the people who existed prior, their stories are often given an additive gist such that the deeper into the future one travels; which is our present, they take a crafting that elevates figures to godlike status. In looking at Alexander the Great’s story and travel to Egypt, where he sought a shrine to declare him a god in his desire to live beyond time, it reveals how he viewed his ancestors. Alexander believed that figures like Hercules and Achilles were originally human beings who, over time, had their mystique upgraded to godlike status. His visit to the Oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis, where he was proclaimed the son of Zeus-Ammon, was a pivotal moment in his quest for divine recognition. This declaration elevated him beyond mortal status, reflecting a deliberate effort to establish himself as a living god, much like the heroes of old whose legends grew with each generation¹⁰. As time travels, their weaknesses are erased and their strengths elevated. In us as beings, there is a general desire to show that we were more than just what we are in the present, that our tribe, our kin, were something legendary. The Three‑Eyed Raven was important in Game of Thrones movie lore because all the stories of this world resided with former Bran Stark; hence that is all this world was not the present conquest, not the present intricacies, but the history of what led to their elevation. In the death of this Three‑Eyed Raven, so did those stories and as such, these two African lores show us this. They also explain the general confusions we have as Africans: with lore this rich, with so present evidence that we were once more than what we see ourselves through our post‑crafted Eurocentric identity that now determines what our Africanness is, we believe without question linguistic classification as evidence of migration patterns, and we lack zeal for our environments and countries because of the failure to solidify such history.

First, we can see three common patterns.

First, foolish love came at a cost: for Mamadi it was his people’s prosperity, which under the circumstances he likely would not have valued, despite his woman being a sight to behold. In Isaza, senseless love destroyed a king and cost him his kingdom, allowing a schemer of dubious morality to ascend the throne with the help of Mr. Downstairs.

Second, these stories demonstrate that we understood good and bad, refuting the notion that primitiveness defined our daily lives. They show that sacrifice for love was innate among us and that we were not merely polygamous primates (there is nothing wrong with loving many women; perhaps if Isaza had loved all seven‑plus of his wives equally, he would not have followed the pretty milk demon downstairs).

Third, there is clear philosophical substance revealed through the riddles present in Isaza’s quest; this echoes David’s deliberation over Uriah the Hittite’s wife after spotting her from the balcony, and similar deliberations quietly haunt both King Isaza and Mamadi.

Furthermore, these stories have educational benefits. We have rarely spent more than one or two lessons on them in history class, we have seldom staged plays centered on them as often as we do Shakespeare, and private financiers of our origins have invested little more than a token of their funds to bring them to film. When they do appear on screen, they are too often reduced to simple tribal incantations, despite holding profound insights. This is not to say there have been no attempts to explore these narratives beyond a one‑page liner in a textbook or a tale narrated by the local tour guide, who is often dining in abject poverty. Such efforts remain minimal at best. I couldn’t prior to my mini enlightenment, to call it that spend two hours on the phone with a baddie telling her about the story of Bida, as I so passionately told one woman about Octavian being a dictator at nineteen and how, if that were me, she’d have sat beside me on that throne for the next twenty‑plus years, as Octavian did. It would have dropped my aura points to have told her about Isaza for two hours. She’d have thought I was a Rafiki‑rocking, struggling poet.

The point I’m making is that we ignore these stories because we do not seek their importance in more than just a children’s pastime. There are larger stakes at play. Identity is built by the stories we pass on to our youth us being the bearers of our future. While the details of those stories can be contested. Whether around a village hearth or in academic halls, where entire professorships study these traditions, just as they do Roman and Greek history this effort isn’t about “them.” We often default to “they” when diagnosing the failures of African education yet “we” either teach liberation narratives (“we, the current ruling party, liberated you from colonialism”) or distant tales of Greek gods and British monarchs. As a Manyika man, I can recite every major event of the Punic Wars, name the only female ruler of Numantia, even explain the rise of the Numidians but I cannot name a single Manyika queen. Those elders who once carried our history in their memories are growing silent, and with them, the context that gives our identity its meaning fades away.

The story of Bida for example is itself a sitting film. No need to tweak anything, and research tells me there have been attempts to translate it as with so many of our African stories, but they’re done with such limited constraints and the form in which they’re presented is often not of the quality that would hook us to inspire an interpersonal cultural fever. It’s therefore important for us to codify these stories first in our education, then in our entertainment culture, and finally they will bear cultural and political fruit in crafting identities. I’m not suggesting that those two stories alone define a standard or yardstick of African History as understanding can challenge different minds in different way, but they illustrate how deeply philosophical and beneficial our traditions can be. Whenever they have been presented with the resources and reach, we aim for, they too often adopt a Western perspective that reshapes and assumes identities, infusing external viewpoints that alienate the very African audiences we intend to engage. We need instead to craft these narratives in their original form hence honoring their authentic context and depth while applying high‑quality storytelling to ensure they truly resonate.

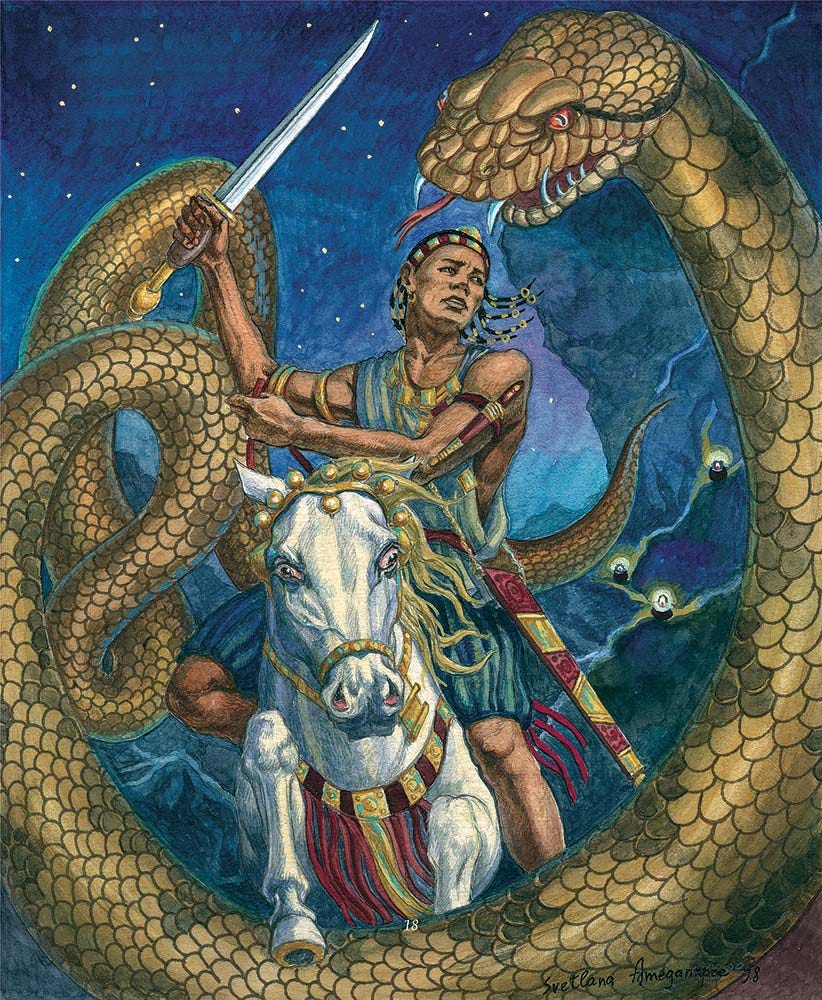

Art by Ana Svetlana Amegankpoé

Conclusion

In truth, these stories aren’t relics. They’re foundations. They’ve simply been left to gather dust while imported narratives shaped our mirrors. The task now isn’t to invent pride, it’s to restore it and to raise these lores to the level of curriculum, cinema, and cultural imagination where they belong. Not for nostalgia, but because they offer the kind of philosophical and political depth that builds esteem, not just sentiment.

We don’t need to imitate anyone else’s myths. We have our own. And until they’re taught, studied, debated, and adapted with the seriousness they deserve, we’ll keep searching outside ourselves for the very thing that’s been sitting in our stories all along.

References

Wikipedia, “Soninke people,” Folklore section (seven‑headed serpent)

Wikipedia, “Ghana Empire,” Ritual and religion section (maiden sacrifices and gold rains)

Diop, Cheikh Anta. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality? (1974)

AncientWorlds.net, “Bida – Soninke legend of the seven‑headed serpent,” Lagarre’s pact negotiation

AncientWorlds.net, same article, Sia Jatta Bari sacrifice narrative

HomeTeamHistory (2019). “The Story of Bida the Seven-Headed Serpent,” YouTube

Wikipedia, “Bunyoro,” Mythology subsection (Nyamiyonga’s riddles and Nyamata)

Harmonia Rosales. Artwork Gallery. Available at: https://www.harmoniarosales.art

[Accessed 6 July 2025].

Adapa, Kwame, PhD. (August 2021). The Nagas, the seven‑headed serpent and migration to different parts of the world [PDF].

Plutarch, Life of Alexander, and Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, accounts of Alexander’s visit to the Oracle of Siwa and his divine claims.

Images used for commentary and educational purposes. Rights remain with original creators. Contact for credit or removal.